“A dictionary begins

when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus, formless

is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to

bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its

form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed

everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be

happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other

goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock

coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is

only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or

spit.”

“Formless” by Georges Bataille, Documents

1, Paris, 1929, p. 382 (translated by Allan Stoekl with Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M.

Leslie Jr., Georges Bataille. Vision of Excess. Selected Writings, 1927-1939,

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press “Formless”, p. 31)

It begins with the planting, growth and

extraction of raw materials that are then processed so thoroughly that nothing

remains of their original form. All that’s left is a macerated pulp, a

formless, fibrous mass, brimming with potential. This mass is then suspended in

water, pulled, drained, couched, and turned into a smooth sheet of non-woven

fibers—a sheet of paper. As a sheet of paper then turns into a page

by being implemented for a specific use, the leaves, soil, rain, wood chips,

bark, all become invisible. Paper emerges from the pulp as temporary,

intermediary—even disposable. It’s luxurious or cheap, durable or frail. It is

used for wrapping, writing, drawing, wiping, and as distance grows from the

sites of production, its formless origins, a sheet of paper is more often the gentle

carrier, in service to an idea, rather than the message itself.

On the glossy pages of a fashion

magazine this transformation is complete. Vogue is printed using M-real's Galerie Fine Gloss

80gsm. These pages are designed, not grown; they echo the

images, the quality desired by the overall editorial scope of the

magazine as they are produced to carry Vogue’s message about fashion, and to be

fashionable themselves. Perhaps Vogue Magazine uses 80gsm coated pulp paper not

only for its brightness and its ability to carry radiant colour well, but also

for its luxurious tactility and the crisp, characteristic sound it makes when

you turn a page—it’s a subtle intermediary for the world Vogue wants to bring

into being. The role it performs is “subliminal” but hidden deeper are the raw

materials, transformed and providing the reader with no idea of the sites and

conditions from which the pages emerged.

In fact, most consumer products

obfuscate the raw materials, sites of extraction, and labour in favour of the designed outcome; origins are

erased by processing and displaced by aesthetic or functional intentions. In

the 1973 ecological dystopian film Soylent Green, Charlton Heston’s

character famously uncovers that the food product served to the downtrodden

residents of New York City in 2022 is made of human remains. This film presents

a resource-strapped deeply environmentally damaged vision of the future and

takes aim at a rapidly globalizing world that had begun to manufacture

petrochemical plastics in staggering volumes, and to shift production offshore,

to blackbox the production of everyday things. It

isn’t a story about cannibalism. Heston’s character is reduced to a desperate,

wounded state, screaming about the suspicious transformation from pulp to

product, happening hidden from view. In the fast fashion and textiles

industries, this market tendency is at an extreme.

The

origins of raw materials disappear in the transformation from fiber to textile,

and as our interaction with the world becomes increasingly dependent on

screens, the design decisions of fashion products tend to be image-driven or

otherwise immaterial. In other words, the desired outcome—for example, a

white T-shirt—dictates the design decisions rather than experimental or

material-led processes that produce a design. In the hyper-speed fast fashion

industries, materials are often incidental and in service to the desired

outcome: a white T-shirt. They carry a design much in the same way a sheet of

paper carries content as a tool in service to an intention; the materials that

animate the design, like the sheet of paper, are often secondary, attendant to

and in service of a larger aim.

The

effect of this distancing from material and social relations can be felt at

both ends of a garment’s life, from its conception as a design object to its

ultimate disposal by the consumer. This action of disposal is a staggering

convenience, with violent ecological and social effects. This gap, or chasm, really, is a

problem. We need critical perspectives on materiality that, with Annmarie Mol,

stubbornly notice the problems and the potential for radical possibilities in the

figuring of pulp. What is radical here is not the possibilities for content to

be carried on a page, which has—for too long—been reified (or burdened) as

merely the carrier of fashion imagery (and knowledge). The page binds content

and knowledge into a specific form: flat, A4, glossy, brightness .75, caliper

width 0.0025, etc. The alternative is the mass of pulp: Bataille’s notion of l’informe, proposed the infinity of its

formlessness and potential, debased and purely material. This allows us to

imagine loops of meaning, as knowledge and matter spiral in and out of the

pulp. Design from pulp can be circular not only in a material sense, but

epistemologically as well: knowledge circulates and emerges differently as

garments and magazines become carriers of possibility.

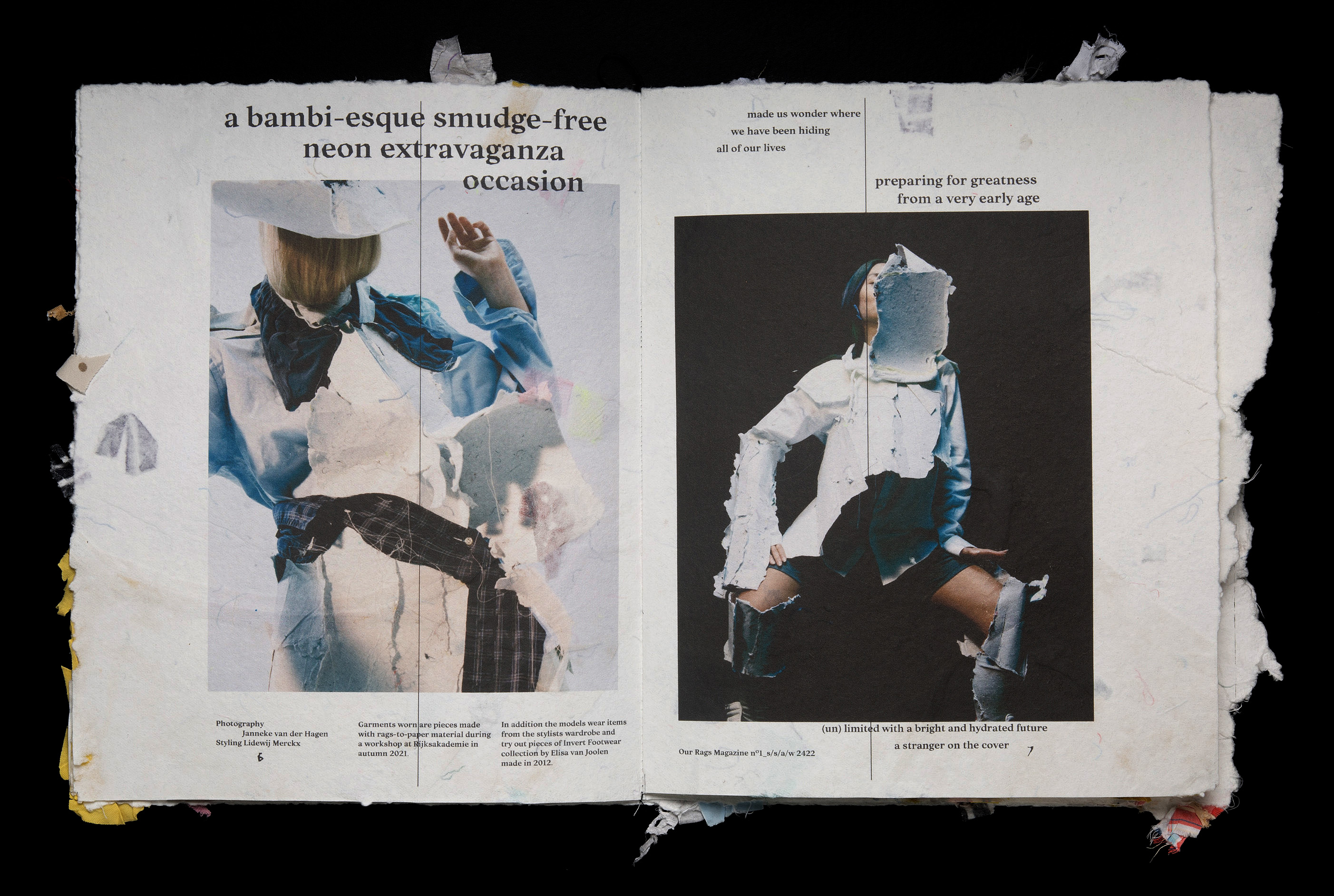

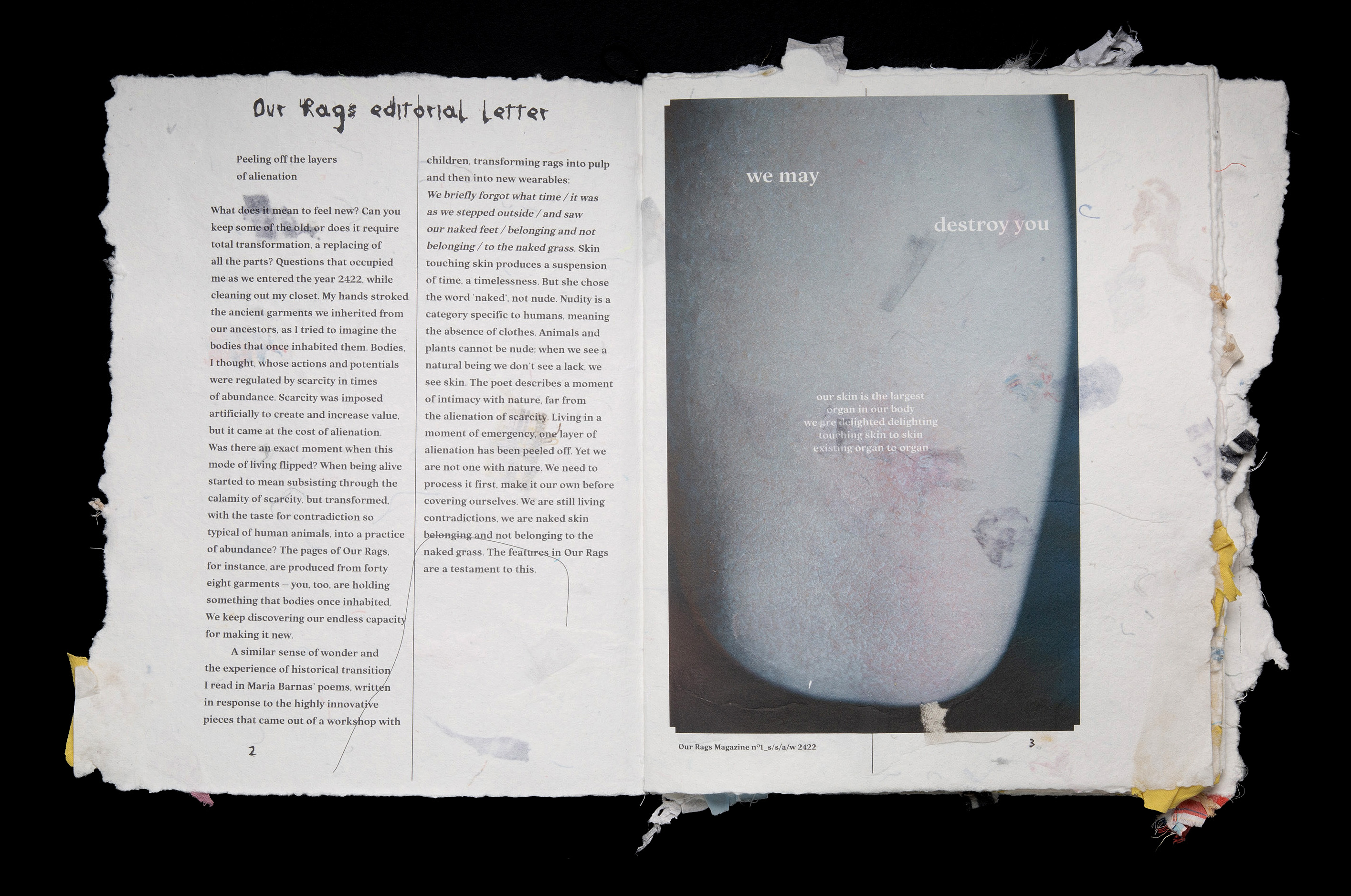

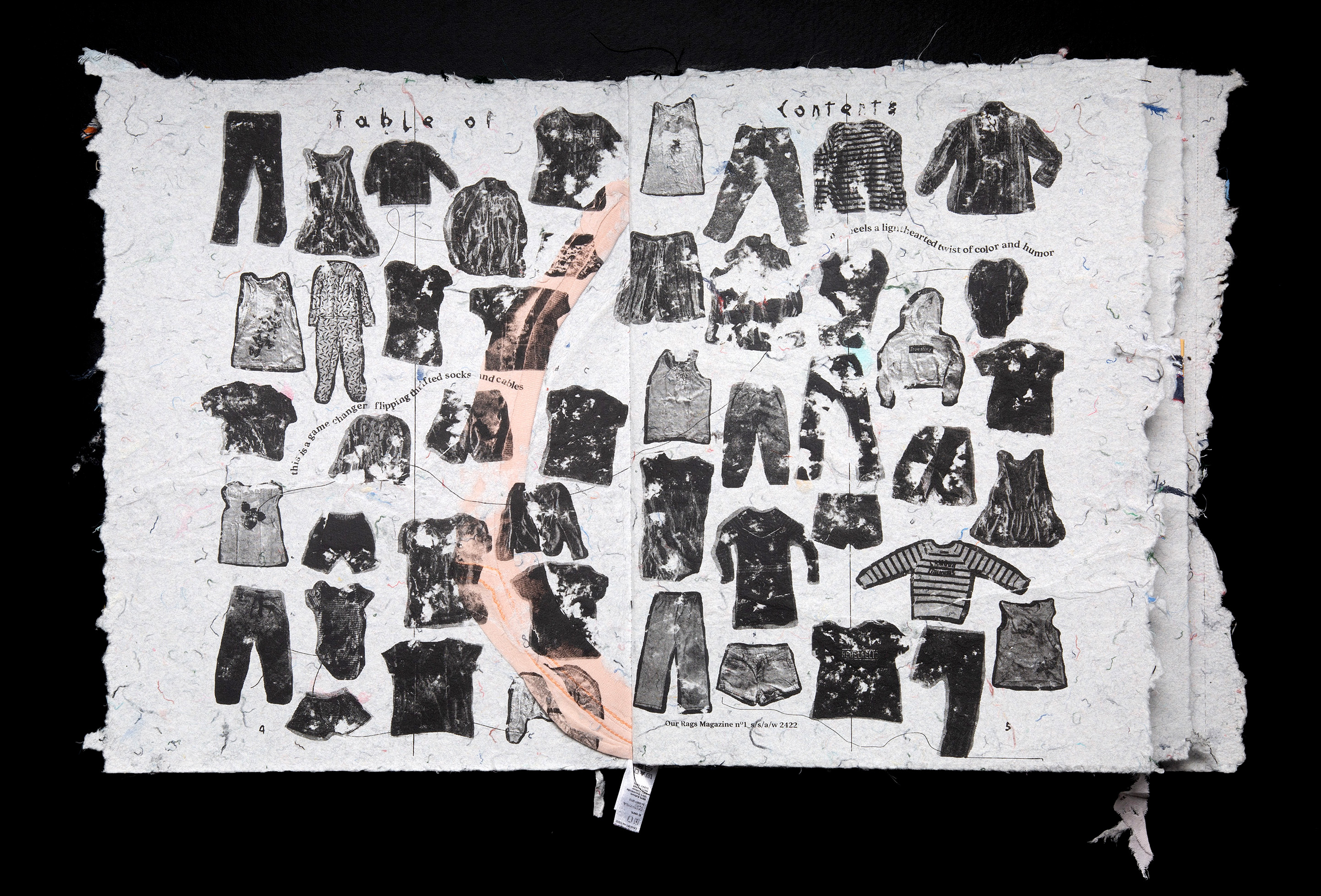

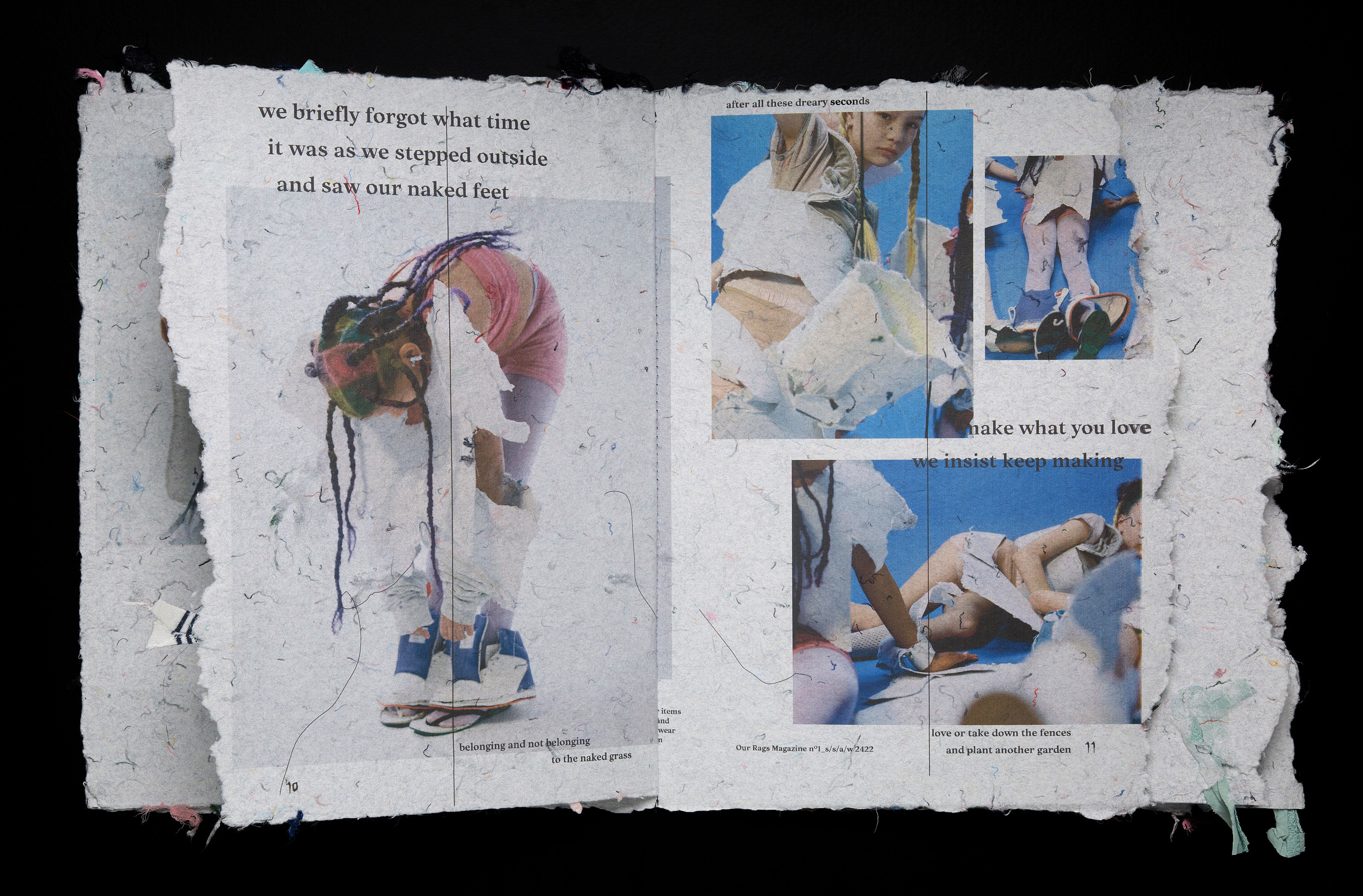

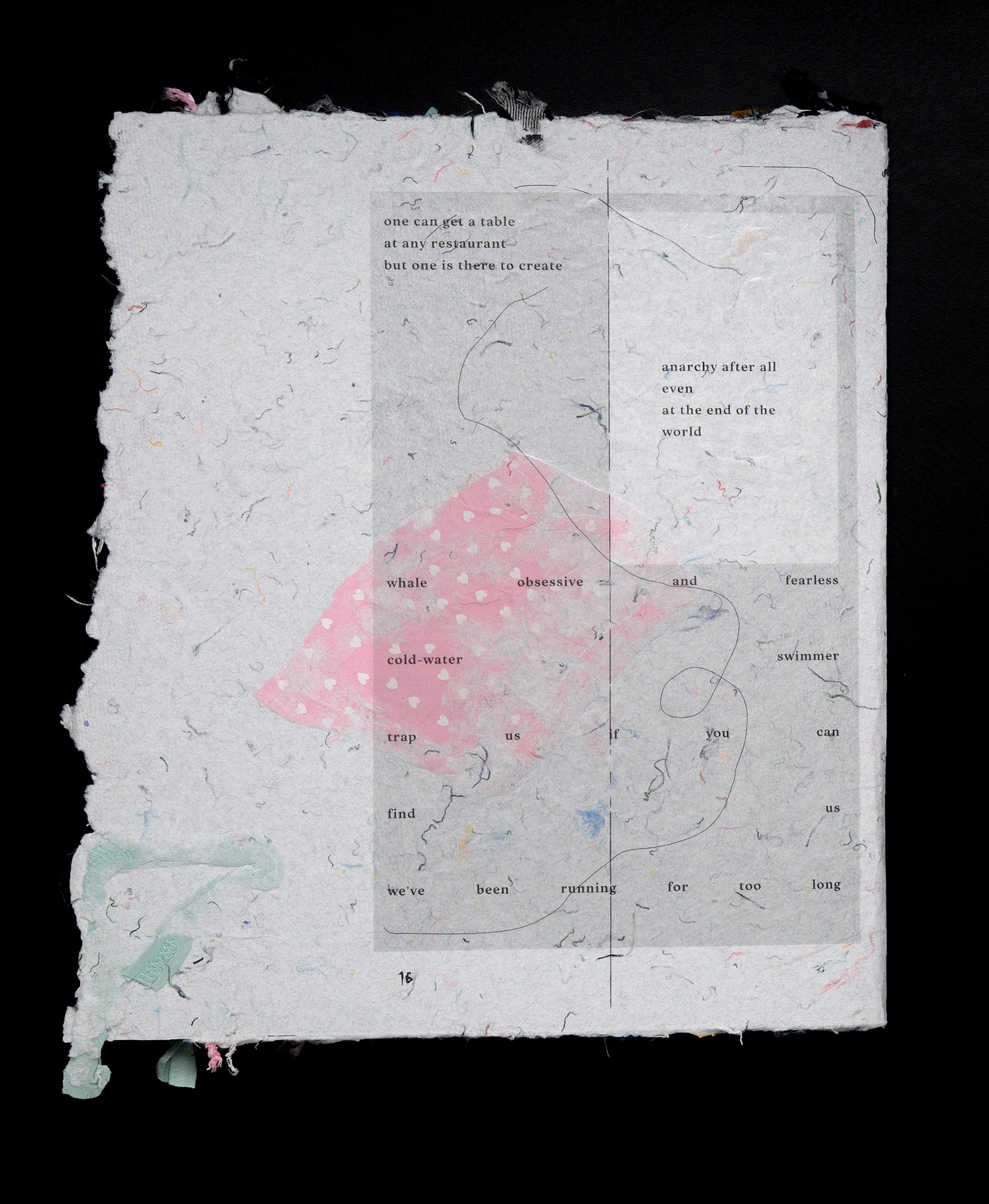

This dynamic is expressed and critiqued

in Our Rags Magazine, a collectively designed

speculative fashion magazine created by visual artist Aimée Zito Lema and

designer Elisa van Joolen. The starting point for this collaborative project is

a projection about the future of fashion magazines, in 400 years when we may

not have the luxury of using new resources to produce Fine Gloss 80gsm coated

pulp paper. Desire always endures, but so do materials. Can we imagine a future

world in which new materials cannot be used for fashion? This speculative

fashion magazine is made of the actual garments presented on its large-format

pages, fragments of which are visibly embedded in or dangling from each page.

Following Donna Haraway’s invitation to consider how knowledge can be situated

within the cultural, historical, and political contexts of the knower, this

project invites the additional question: what could a situated material

practice be? The rough texture of these pages is defined by threads, fibers,

shreds, and stitches—this is about representation and knowledge; the paper

is the content and the medium. Our Rags Magazine manifests a critique of the

obfuscation so common in the fashion industry by offering a

radical inversion of Vogue's 80gsm. In other words, by turning clothes

into paper, it overtly leaves material traces of its production and refuses the

smooth separation between medium and content. Where the flat, white, glossy

80gsm paper disconnects us from the web of relations, these pages invite us to

consider the macerated pulp, the formless fibrous mass, and the conditions of

production—and that things can run out.

Dystopian or utopian, paper clothing can

represent a vision of a future for manufacturing and fashion. In 1966, to sell

more disposable paper products, American firm Scott Paper ran a campaign in

which they offered two disposable paper dresses, printed to match the

napkins and place settings, any customer who sent in a redeemable coupon and

one dollar. This ignited a two-year fad in North America and Western Europe

that represented an optimistic vision of the future—one in which we humans can

have whatever we want at a very low price, and simply throw it away once it has

exhausted its physical or social potential. Despite this relatively recent

Space-Age innovation, paper was not originally designed to be disposable, and

its earliest forms are durable, circular, and regenerative.

In this project, Zito Lema and van Joolen are drawing

from a long history of early forms of paper that were emerging in Western

Europe in the 11th century—paper made from hemp, linen, cotton and

flax rags. The origins of papermaking can be traced to the Chinese court in 105

CE and was made of plant fibers and silk and cotton rags. The

fundamental steps to produce a sheet of paper haven’t changed much since its

inception in China, from fiber to formless fibrous slurry, to sheet via a

screen of some kind. As the skills made their way along the silk road to

Western Europe, adaptations were made. Plant pulp was not the most common

material for papermaking in Europe until the 19th Century. Until

then, the papermaking industry was reliant on repurposing used clothing and

other textile material, often collected or scavenged by a

“rag-and-bone-man", sorted, detangled, unpicked, unadorned, sliced,

macerated, and turned into a pulp for the papermaker. Since the raw materials

were often scavenged or free in the form of discarded bedlinens, fishing nets,

or clothing, rag paper was cheap and readily available. In fact, recycling was

at the core of the papermaking industries in Europe until German engineering

invited pulp paper production to take hold in the early 19th

century. Holland would eventually become one of the leaders in rag paper

making, providing an example of a “circular economy” before the need to label

it as such emerged. Continuing this history, Zito Lema and van Joolen engaged

the help of the volunteers who run the steam-powered paper mill in Loenen (NL),

where cotton rag paper has been produced for over 400 years.

Our Rags Magazine is part of Pulp, an ongoing

project by Zito Lema and van Joolen, where the pair explore the possibilities

for recycling garments into paper via the use of traditional and

nonconventional methods. Our Rags Magazine is at its core a community

practice and was shaped collaboratively via public workshops with children, who

were encouraged to consider how they use and value clothing, and to imagine

radically different ways of dressing and creating garments. Workshop

participants contributed their own garments to be shredded and transformed into

sheets of paper at the Dutch windmill in Leonen. These would later become the

pages of the magazine, and then garments once again; once the pages of the

magazine had been assembled, the participants were given sewing machines,

Velcro, tape, scissors, and pins, and invited to turn the rag paper sheets made

of their garments into new garments.

The traditional European rags-to-paper

is taken another step further as the rags transform to paper and then back to

garments again. This is how a garment in a magazine, is a magazine. A garment

is shredded and transformed into a sheet, becomes a page carrying images of

itself, and is then worn again as a garment. A fundamentally different

relationship between fashion garments and editorial content appears here. In Our

Rags, each swap places after passing through a state of formlessness. From

garment to paper, then to page, to garment again, the cycle suggests an endless

recursive loop of form and content. This was a chance for the young

participants to experience circularity first-hand, a term which has now become

commonplace in our vernacular, but often understood as the domain of companies,

who recycle plastic in enormous, often unseen facilities in Asia.

The editorial fashion

content in Our Rags Magazine embodies this approach to tactile

circularity. Text, image, and paper stock, like any conventional magazine, are

the three ingredients of this publication, but here the editorial aspects (text

and image) of the magazine were created in response to the material parts (paper).

As vehicles themselves, the handmade paper pages carry text and photographs in

various mediums, printed using innovative techniques, as conventional printers

could not handle the material. The magazine is designed by Elisabeth Klement

and includes contributions by photographer Janneke van der Hagen and writers

Maria Barnas and Persis Bekkering. This project emerges from the conditions of

practice—messy and collective—and doesn’t endeavor to hide them. This is not

just about garments, but the knowledge, the editorial content, also surfaced as

the matter of fashion. This

magazine is not just about fashion, it is fashion itself, materially.

Unlike traditional fashion magazines like Vogue, who obfuscate this, and may

consider paper as a vehicle or flourish, the content in Our Rags Magazine

was created in response to the pages themselves to cut through the white noise

of fashion imagery: celebrity, sponsorship, or commerce. By breaking down the

garments into a fibrous rag pulp, the artists can break limits and boundaries

of the fashion image, of the garment and how it can be presented, and even the

material object itself, and how it can exist. They are testing the ways

a garment can be formless and brimming with self-generating discursive power.

This is a proposition for challenging the finite boundaries of an object by

simultaneously transforming it into a material carrier and subject for

representation. The artists render the multiple lives of a garment in order to

explore the infinity of existing objects and materials. Post-use, objects and

materials do not stay the same, but they carry with them echoes, imprints.

Desire endures, as do materials. As we progress along our timeline of

high-volume production, what does the future look like?

Sinking garbage islands shedding secondhand clothing onto beaches in Kenya and clothing dumps in the Atacama Desert have become familiar sights in our newsfeeds. There is lot of messaging from brands about changing their modes of production, and research into how consumers can change their patterns of consumption and use to avoid the stupendous surplus produced in fashion. Despite this, if the tendency towards "sustainable” production does not engender a reduction in waste or a violent break with the past, then perhaps it is conceivable that in 400 years we would have even more sedimentary layers of discarded textile materials embedded in our landscapes. Are we creating layers for future excavation? Historical records of a moment in time when we made too much? Or simply the base layer on which to continue to pile on more—a rotting, very slowly degrading mixture of soil, sand, insects, mold, fungi, natural fibers, plastics, all the images on the pages of fashion magazines, the fast fashion #hauls on TikTok, and all the white T-shirts that came from origins unknown. All this deposited, no longer individual units but interwoven, formless, garments transcending categories, becoming a slurry in the Earth. A pulp. Our Rags Magazine becomes the fashion magazine of this future.

About the writer

Dr Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran is an academic and designer working in the School of Fashion and Textiles at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. Her area of expertise is interspecies collaboration and paper clothing in various cultural contexts. You can find out more here: d-mvp.com (IG: @daphne_mvp), dnj-paper.com (IG @dnj_paper).

About Our Rags Magazine

Imagine what a fashion magazine would look like in 400

years. In a world with no natural resources left, transformation and recycling

are the only way forward.

Our Rags Magazine is a collaborative project by Aimée

Zito Lema and Elisa van Joolen that investigates transformative processes,

proposing new forms of collective production aimed at the reuse of discarded

clothing and textiles. The project and resulting magazine question consumer

behaviour and its relationship to the world in which we live. Further expanding

the potential of recycled material, Our Rags Magazine is a magazine where the

pages not only show clothing, but actually are clothing.

The project started in 2019 with a workshop in which

children were invited to imagine new ways of creating garments and new ways of

dressing. The workshop revolved around dissecting discarded pieces of clothing

brought in by the participating children. Subsequently, all garments were cut

into small pieces and recycled into a new material: paper. A Dutch windmill in

Loenen (NL) which still masters the age-old technique of transforming old rags

in cotton-based paper transformed the shredded garments into coarse and tactile

paper sheets that form the material base of Our Rags Magazine. Returned to the

workshop participants, the kids collectively made highly imaginative garments

from the rags-to-paper material.

Our Rags Magazine pushes the possibilities of recycled material even further. By manufacturing a fashion publication that is printed on this very material – creating a magazine of which the pages don’t merely show the garments, but are the garments – this project shows the creative potential recycling garments and textile can offer.

Designed by Elisabeth Klement, the magazine contains contributions by photographer Janneke van der Hagen and writers Maria Barnas and Persis Bekkering. The project was supported by Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam and the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds.

Published by Warehouse | A Place for Clothes in Context.

More informarion about Warehouse: www.thisiswarehouse.com

Our Rags Magazine: IG @ourragsmagazine

Image credits:

Our Rags Magazine, Aimée Zito Lema & Elisa van Joolen, 2022. Dimensions: 340 mm x 310 mm, paper made from used clothing. Graphic design by Elisabeth Klement, photography by Janneke van der Hagen, styling Lidewij Merckx. Publisher: Warehouse.